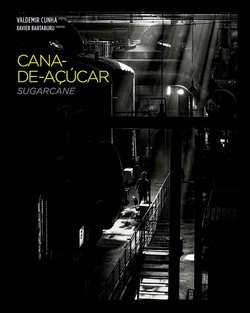

CANA-DE-AÇÚCAR

|

The honey of the fields

Nobody knows who the first person to taste the sweet flavor of sugarcane was, but we do know that this thirsty individual was an inhabitant of New Guinea. It was there, around 8000 years ago, that the first sugarcane seedlings were cultivated by human hands. At that time, sugar had yet to be discovered – people consumed the plant’s syrup by chewing on the stems. And this was a considerable source of energy in that area of the Pacific, especially useful in the long canoe journeys that people often made around the archipelagos. And as such, from island to island, sugar cane slowly made its way across Indonesia until it reached continental Asia. It took hundreds of centuries to do so, because the earliest records that we have of important plantation zones in northern India date from the last millennium before Christ. It was there that sugarcane as we know it first appeared, after the formerly wild species was crossed with local species. We are also indebted to the Indians for the creation of the first milling devices used to extract sugarcane juice – a fact which quickly led to the discovery that, by boiling the syrup, it was possible to crystalize the sucrose and then store it for months. At it this time, it was sugar in its most rudimentary form, not much different from the rapadura that is consumed in Brazil today. The method for obtaining it, incidentally, was the same: by decanting the syrup, a technique which would cross oceans and centuries until arriving, relatively-unchanged, at the sugar mills of colonial Brazil. It’s impossible to determine the moment when sugar started being manufactured, but the oldest records on the subject, dating from the 5th century BC., already account for a series of products derived from sugarcane. In India, in addition to the ancestral jaggery, they produced crystal sugar (known as khand) and grain sugar, not yet refined, which resembled sand. Hence the name in sanskrit: sharkara (“gravel”), a term later borrowed by the Arabs (al-sukkar) and which would give origin to the word “açúcar” in more than 40 languages. News of sugarcane arrived in Europe around this time. Precisely in the 4th century BC, when Alexander the Great’s troops invaded India and came back speaking of “bamboo that produces honey without the need for bees.” From India, the cultivation of sugarcane spread across Asia along with the technology for sugar manufacturing. First to China, then to Persia and the Arab world in the first centuries after Christ. The work of adapting the Indians’ techniques fell to the Arabs and they honed the quality of the sugar, finding ways to filter impurities and make it whiter. They created the first refineries, as well as the first large plantations, supplied by an ingenious system of irrigation. The Arabs were also responsible for the rapid spread of sugarcane cultivation, especially from the 7th century on, when Islam began its period of expansion. Wherever the Koran went, it was almost always accompanied by sugarcane seedlings. This is how sugarcane came to the Mediterranean. As early as the 10th century, we have records of plantations in several areas that were under Muslim rule, including Sicily, North Africa and southern parts of the Iberian Peninsula. Still, regular trade with European nations was only established after the Crusades, when the city of Venice, the great mercantile power at the time, took over the monopoly of the routes that connected the Middle East to the ports of Europe. It was then that sugar began to sweeten western taste buds. First, it was limited to the tables of the wealthy. Then, eventually, it was used as a remedy for stomach and kidney ailments, in the form of hard candies seasoned with aromatic herbs. In the following centuries, Venice also began taking control of the production, installing refineries on such islands as Malta, Cyprus and Crete, bringing the sugar industry closer to Europe’s consumer market. Still, the big increase in production would come thanks to the Portugal and Spain in the 15th century. Both countries were familiar with sugarcane because of the Arabs, who had, at that time, just been expelled from the Iberian Peninsula. Both countries had also just discovered-- and occupied – islands in the Atlantic located at latitudes below the Mediterranean, and therefore had better conditions for cultivating tropical plants. In this way, places like Madeira Island, the Azores and Cape Verde – Portuguese territories – and the Canary Islands, controlled by Spain, aside from serving as stopovers for overseas expeditions, quickly became the regions par excellence for the expansion of sugar plantation. Madeira Island possessed the best conditions and, in less than a century, it had turned into the biggest sugar producer and exporter in the world. Between 1432, when the first mills were built, until the end of the 15th century, production jumped from 70 tons per year to 1200. No small feat when considering that, at the time, sugar was still a rare and expensive ingredient, with a market value 40 times what it is today. Incidentally, sugar was often donated to charity institutions like convents – a fact which favored the development of desserts among Portugal’s nuns. Throughout at least 150 years, Madeira Island’s entire economy basically revolved around sugar, involving over 15,000 people – from Jewish merchants to thousands of enslaved Africans. The island was Portugal’s big laboratory for sugarcane cultivation, where the production model that would later be applied in Brazil’s sugar mills was largely established. But it wasn’t the Portuguese who first brought sugarcane to the Americas. This deed is attributed to Christopher Columbus, whose ships carried seedlings from the Canary Islands on his third expedition to the New World in 1498. When the first plantations were installed on the island of Hispaniola – today home to Haiti and the Dominican Republic –, the Spaniards realized that sugarcane grew at a speed never before seen anywhere else in the world. The plant, after all, had been reunited with its latitudes of origin – the same tropics of intense sun and abundant rains that allowed for its development in India and the Pacific. But this time, the soil was even more fertile. Less than 20 years after Columbus’s arrival, a sugar industry was thriving in the Caribbean under Spanish rule. Islands like Cuba, Jamaica and Puerto Rico were packed with sugar mills. THE MILL ERA In Brazil, the first sugarcane seedlings came along with the seeds of the first city, São Vicente, founded in January of 1532. Both were initiatives of Martim Afonso de Sousa, whose sense of entrepreneurship would earn him, that year, a title of endowment of the captaincy which was named after him. He was also the man who built what some historians consider to be the first sugar mill erected in Brazilian territory – Engenho do Governador, later known as Engenho dos Erasmos. Several others just like it sprouted up in the vicinity of São Vicente, which soon became one of the colony’s most productive regions. They say that, in the 16th century, sugar itself was used as currency in the village. It also didn’t take long for sugarcane plantations to be established in northeastern Brazil. In 1535, Duarte Coelho, endowed with the captaincy of Pernambuco, established the first sugar plantations and Jerônimo de Albuquerque, his brother-in-law, set up the first sugar mill in the region, Nossa Senhora da Ajuda, on the outskirts of Olinda. There, growing conditions were even more favorable; not only was the sunshine brighter, but the extremely fertile massapé soil allowing the plantations to expand rapidly. Furthermore, northeastern Brazil was closer to Europe than São Vicente, making for shorter ocean voyages. During the same period, these factors favored the rise of yet another production center in northeastern Brazil, in the surroundings of the colony’s recently founded capital, Salvador. The establishment of sugarcane plantations was so successful in Brazil that, by the end of the 16th century, there were already 120 sugar mills in operation. Three decades later, around 1630, that number had tripled: approximately 350 mills were spread across the country’s coast, concentrated in Pernambuco and Alagoas, in Recôncavo Baiano, in southern Bahia and at points in southwestern Brazil – mainly on the coast of São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro and Espírito Santo. Together, they produced the equivalent of 13,000 tons of sugar, with an export value higher than 3.5 million British pounds. This was the height of the boom. At that time, Brazil had become the biggest sugar producer in the world, the nerve center of a global trade that involved three continents. In Africa, several kingdoms profited by selling people to the slave traders who operated the ports, responsible for exporting slave labor to the sugar plantations and mills of Brazil. From Brazil, the raw sugar was packed into boxes and transported to Portugal, and then reexported to Amsterdam, where it was distributed throughout Europe and transported to refineries that had been built on the outskirts of the city. From Europe, the ships, in turn, sailed back to Africa and Brazil, this time loaded with manufactured products like clothing and jewelry, used as merchandise in exchange for slaves as well as to meet the demand for luxury among the plantation owners. Because of this international network, which stretched across the Atlantic, sugar is considered the first commodity to be commercialized on a global scale, the effects of which – direct and indirect – influenced the most diverse sectors in the 16th and 17th centuries. In addition to stimulating the slave trade and maritime transportation, sugar also propelled the European manufacturing industry and naval construction, as well as the insurance business, favored by the number of attacks by pirates which led to elevated losses in merchandise. The European palette was also affected, because sugar now reached the dinner tables of the greater population more readily, replacing honey as the preferred sweetener once and for all. Baked desserts as we now know them emerged precisely during this period. In Brazil, especially in the plantation zones, a society arose which was almost entirely subordinate to the sugar mills. They were veritable cities, 100% self-sufficient, where there was no need even for nearby villas. When they did exist, they were most often ports for sugar overflow. Practically the entire social, economic and religious life at the time was limited to the plantations. In addition to sugarcane crops, the grounds also contained subsistence farms, pastures for the animals that transported the sugarcane and moved the mills and even stretches of forest, to guarantee wood to heat the cauldrons. There were also workshops where carpenters, blacksmiths and tailors worked, as well as an infirmary, a chapel and a still. As many as 200 slaves slept in the slave quarters. And in the main house, where the mill owner and his family lived, the number of domestic slaves could include up to 60 people. It was the most eloquent portrait of colonial Brazilian society: the Africans – and the natives, initially – as the workforce for the physical labor; the mulattos, people of mixed-race and poor whites as free laborers, specialized in mechanical trades; and the rich whites as the landowners. The mills worked according to the plantation model, an agricultural system developed by the Portuguese on the islands in the Atlantic which presupposes the existence of a latifundium dedicated to a monoculture, whose production was focused on exportation and whose workforce was essentially made up of slaves. In Brazil, this system became so effective that it ended up being replicated in various colonies in the Americas, and was also applied to other crops, such as coffee and cotton. It was, in fact, the world’s first model of large-scale agribusiness. Though rudimentary, the sugar factories in colonial Brazil were highly sophisticated for the time, since it guaranteed productivity by setting up a very well-structured production chain, where the work was divided into dozens of specialized functions. There was the sugar-master, the steamer, the vat mixer, the furnace stoker and many others, each one responsible for one step in the long process that transforms sugarcane juice into sugar. Regarding the physical structure of the mill, it was divided into three parts: the mill device, which could be moved by water (in mill located on a river or stream) or by animal traction (in landlocked mills); the cauldron house, where the syrup was cooked in giant copper bowls; and the steam house, where the syrup produced from the cooking process – the honey of the mill – was placed to decant and crystalize in conical forms. Forty days later, the so-called sugar load was ready, a sugary cone which, in turn, was submitted to a procedure called “mascavar” in Portuguese. Here, white sugar, which was designated for trade and for the mill owners’ personal use, was separated from brown sugar, concentrated at the end of the cone (since it was there that the honey accumulated during the crystallization process). This brown sugar, known as “açúcar mascavo,” the kind richest in nutrients, was given to the slaves. The crystallization process also yielded a byproduct: the drip honey, or molasses, a remnant of the cooked sugarcane syrup which seeped out of the orifice situate at the end of the mold. This honey, when fermented and distilled, gave way to cachaça, the beverage whose production in Brazil began almost simultaneously with that of sugar. Incidentally, all evidence indicates that the liquor is an exclusively Brazilian invention, the result of the employment of distillation techniques brought over by the Portuguese – used in the production of bagaceira, a grape liquor – applied to the sugar molasses. In the beginning, the slaves were the only ones to consume cachaça. And with the consent of the mill’s master, since it was believed at the time that the drink made them more docile and more disposed to work. Only in the 17th century did the beverage take on commercial value. It left the slave quarters, entered the main house and ended up captivating the population throughout the entire territory. So much so that the Portuguese crown needed to tax the liquor so that it wouldn’t compete with the bagaceira imported from Portugal. This measure caused the Cachaça Revolt to explode in Rio de Janeiro in 1660. The sugar mills also saw the beginning of production of rapadura in Brazil, a technique that was likely imported from the Iberian islands in the Atlantic. Like sugar, it results from boiling the sugarcane juice, but at a different cooking point, something that allows the sucrose to crystallize more rigidly. This favors both storage and transportation-hence its popularity among the travelers who crossed Brazil in the days before the railroads. Furthermore, rapadura retains a large part of sugarcane’s nutritional properties, including various vitamins and minerals like calcium, iron, phosphorus and magnesium. It is, to this day, one of the Brazilian people’s great sources of energy. Especially in the backlands, where resources are scarce. The production model employed by the mills in colonial Brazil was so efficient that it remained unaltered for three centuries. It only changed in the early 1800s century when the first vapor mills appeared. Still, the advances of modernity did not save Brazilian sugar from the crisis that was in full force at that time, the fruit of a process begun a century and a half earlier. The year 1654 to be exact, when the Dutch were expelled from Pernambuco, after nearly three decades of occupation – but not without taking some sugarcane seedlings with them. The destination for these seedlings was the Antilles, a Dutch colony where Holland quickly set up a promising sugar industry. Considering that the Dutch was also a key part of the sugar market, Brazil suffered a double impact: not only did they now have another competitor, but they also lost a commercial partner. Soon, the French and the British followed Holland’s example and also took it upon themselves to plant sugarcane crops in their Caribbean colonies, increasing competition as well as offer, a fact that cut the product’s market value in half. By the end of the 18th century, Brazil had lost its sugar monopoly. Jamaica and Haiti were now the biggest producers. An even bigger blow came in the early 19th century, when the continental blockade imposed on France by the British navy led Napoleon to encourage the search for an alternative to the importation of sugarcane. The result was the emergence of beet sugar, the consumption of which didn’t take long to spread all over Europe. Affected by all of these factors, Brazil’s imperial government, with its newly-conquered independence, invested in the production of coffee, which soon took the lead – up until then, sugar was still the leading export, ahead of gold, even during the height of the mining boom. The numbers speak for themselves: in the 1820s, sugar represented 30% of the wealth of all exports, compared with coffee’s 18%; by 1889, the year of the proclamation of the Brazilian Republic, coffee accounted for 60% of total exports, while sugar was under 10%. Conscious of the need to modernize the country’s sugar production, Dom Pedro II created the Engenhos Centrais (literally “The Central Mills”) in 1875. The idea was to separate the fields from the factory; in other words, to encourage, through subsidies, the construction of vapor plants dedicated only to sugar production, and no longer farming the actual sugarcane crops. This work would fall to the owners of the mills, now relegated to supplying the raw material. Aside from increasing productivity, it would also be a way to get around the shortage of manpower that resulted from newly-passed abolitionist legislation like the “The Free Womb Law,” passed in Brazil in 1871 with the ostensible intention of freeing children born to enslaved mothers from that date on. Still, the implementation of the Engenhos Centrais was hampered by the refusal of the mill owners to let go of their concentrated power. This was especially true in northeastern Brazil, where the colonial tradition was stronger. Meanwhile in São Paulo, the profits from the coffee industry allowed the farmers to view the Engenhos Centrais as an opportunity to diversify their sources of income. It was there, nearby the coffee fields, that these mills were most successful. Over time, they provided the base on which the state’s sugar-alcohol was built. A NEW HEGEMONY The first modern sugar mills in Brazil appeared in the late 19th century. Partially a result of the natural evolution of the emperor’s Engenhos Centrais, but also as a consequence of their failure. Sugar producers soon noted that the separation between the fields and the factories was not very efficient, since the supply of sugarcane was irregular, and not always of good quality. Given the high level of investment in these factories, the yield was almost always short of ideal. The government of the Republic, noticing the stalemate, undid the division of the production chain, making room for the owners of the Engenhos Centrais to have their own sugarcane plantations. In addition, it created incentives for the implementation of new factories. These measures attracted foreign groups (French and British, mainly), which, partnered with big sugar producers, started buying crops from the suppliers – it was then that the first mills with total control of production emerged. This took place both in the central-south and the northeast regions, where mill owners with more political and economic power also had the opportunity to invest in modernizing their facilities, going from suppliers to factory owners. All of this allowed for the quick spread of mills throughout the country: in 1910, there were 187 sugar factories, two thirds of which were located in northeastern Brazil. Meanwhile, in São Paulo, the new mill owners worked to assure their place at least in the state market, which was still dominated by higher quality sugar from the northeast. Incentives from the province’s government helped, but the definitive impulse came with the coffee crisis in the first three decades of the 20th century, leading producers to focus their effort on sugarcane. The wealth inherited from the coffee plantations, the offer of immigrant labor and an efficient transportation network – which reduced the costs of distribution – allowed the São Paulo producers to concentrate on improving their crops and honing the production process. In Piracicaba, where the land wasn’t favorable to coffee growing, a prosperous sugarcane region was quickly established. In the early 1930s, the competition between the sugar of the northeastern and central-southern regions of Brazil was in full swing, a fact which led to a crisis in overproduction, in which the offer exceeded the internal demand. The solution came from government headed by Getúlio Vargas with the creation of the Institute of Sugar and Alcohol-- the IAA--, a state mechanism for intervention which, among other measures, established production quotas and exerted rigid control on prices. As the name indicates, there was also an interest in fomenting the burgeoning ethanol industry – which, at that time, presented the best solution to the issue of overproduction. The Brazilian government had been experimenting with sugarcane alcohol since the 1920s, in reaction to problems in oil supply that resulted from World War I. The objective was to reduce the nation’s dependence on imported fuel and, at the same time, encourage Brazil’s sugar industry. The tests, realized by the Experimental Station of Fuels and Minerals (today the National Institute of Technology) culminated in the emergence of the ethanol-fueled vehicle in Brazil: a Ford model T with an adapted engine, which circulated in the streets of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo in 1925. The success of the experiment led to the government’s decision, even before the creation of the IAA, to establish, in 1931, an obligatory addition of 5% of anhydrous ethanol to the gasoline which supplied the nation’s automobiles. Another of the IAA’s objectives was to protect the mills in northeastern Brazil, where the facilities appeared to be incapable of competing with the sugar from the south. Still, government intervention wasn’t able to slow down the expansion of the sugar plantations in São Paulo, a state whose economy grew at a proportion above the national average. The enriched São Paulo mill owners not only modernized sugar production but they also turned their attentions to ethanol, encouraging research and investing in technology. This was crucial during the World War II era when the difficulty of importing oil greatly increased the demand for alcohol fuel. In certain parts of the country, the proportion of anhydrous ethanol in the mixture with gasoline was as high as 42%. At the same time, maritime conflicts presented a serious obstacle to the distribution of sugar produced by the mills in northeastern Brazil, which took place by cabotage. Meanwhile, the benefits for São Paulo during the war were twofold, with an increase in ethanol production as well as access to markets which, until then, had been dominated by the sugar from the northeast. The expansion can be understood by the IAA’s official statistics: in 1940, São Paulo produced 2.7 million tons of sugarcane; in 1946, shortly after the end of the war, this amount had doubled to 5.4 million. That year, for the first time, São Paulo processed more sugarcane than Pernambuco. It was the end of a hegemony that had lasted four centuries. The 1950s saw a definitive change in the gravitational pole of Brazil’s sugarcane industry. While the more obsolete mills of the northeast were turning off their cauldrons, production in the central-south region increased considerably with each harvest. There was also a change in the focus of production: ethanol, overshadowed by investments in Brazilian oil exploration, disappeared from the spotlight to make room for sugar, which made a comeback, again attracting the attention of the international that ran entirely on ethanol, was introduced. It was so successful that, by 1985, nearly 96% of the automobiles sold in Brazil came with alcohol engines. The streets and highways were filled with the largest automative fleet fueled by a renewable energy source – approximately 4 million vehicles-- in the entire world. The Proálcool program started losing steam in the mid-1980s when the high international price of sugar led mill owners to change the focus of their investments. While ethanol disappeared from gas stations, leaving millions of car owners in the lurch, the price of oil fell substantially, making the use of gasoline once again an advantage. As a result, in 1988, of every ten automobiles for sale at Brazil’s car dealerships, only one was ethanol-fueled. By the end of the 1990s, alcohol-fueled cars accounted for less than 1% of the total. Pró-Álcool had failed, but it would leave an inheritance of nearly 5 million hectares of sugar plantations (roughly double of what had existed when the program began) and thousands of gas stations equipped with ethanol pumps. A COUNTRY DRIVEN BY ETHANOL In the years following the end of Proálcool, the only reason that production of the sugarcane fuel in Brazil didn’t stagnate entirely was the fact that, as a means of preserving the sugar-alcohol industrial park, the government maintained the mandatory addition of anhydrous ethanol to gasoline, at proportions varying from 20% to 25%. This measure was crucial for the viability of the automotive revolution that was to come. And it didn’t take long to arrive. In the first years of the 21st century, the oil market already showed new signs of instability, with an increased risk of a new worldwide energy crisis. On the one hand, the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, stemming from the reaction to the September 11th attacks, aggravated tensions in the Middle East, compromising access to the oil wells in the Persian Gulf. On the other hand, rising consumption in China and India and the decline of the oil fields in North America signaled the risk of an oil shortage. These combined factors resulted in a progressive increase in the price of oil. The same strategic motives which had led to Proálcool in Brazil thus led other nations to seek new energy sources. However, this time, these motives were added to environmental concerns which emerged around the turn of the century, especially in industrialized nations. Issues such as carbon dioxide emissions and sustainability in the production chain made all the difference. In this way, almost simultaneously, countries around the world focused their research on the development of more efficient, more economical and cleaner, renewable fuel sources. While Europe invested in biodiesel, other nations turned to ethanol obtained from a variety of sources of biomass, such as corn, wheat and beets. In Brazil, sugarcane once again took center stage. Despite its failings, Proálcool left a considerable legacy in the country, including hundreds of plants in working conditions and thousands of gas stations equipped with ethanol pumps. All it took was the technology necessary to avoid a crisis in supply which had led to the program’s failure. This is what engineers worked to find from the 1990s on: a way to develop engines that could run on both gasoline and alcohol, so that the market would be protected from the oscillations to which both fuels are subjected. The resulting technology was a pioneer in the world: thanks to electrical sensors installed in gas tanks, consumers were able, for the first time, to fill their cars with the fuel that best suits them, at any proportion. In 2003, the Gol 1.6 Total Flex, the first hybrid vehicle sold in Brazil, hit dealerships. Right away other automakers followed Volkswagen’s example and, hand and hand with sugarcane mills, they flooded the nation’s market with flex vehicles. In just five years, biofuel automobiles accounted for 75% of total new car sales in Brazil. Another accomplishment came at the pumps: four out of ten Brazilian drivers opted to fill their tanks with sugarcane alcohol. After all, aside from being ecological, ethanol was also economical: at certain times, it was priced as low as 60% of the value of gasoline. The increase in consumption, as was expected, propelled the entire sugar cane production chain in Brazil. In the fields, the volume of production – measured in tons of ground cane – jumped from 320 million in the 2002/2003 harvest, when flex cars were introduced, to 600 million in the 2009/2010 harvest. What had taken the country 500 years to produce practically doubled in less than a decade. The industrial parks also multiplied: during this same period, the number of mills rose from around 280 to over 430. Including factories and plantations, the sector closed the decade employing around one million people, counting direct and indirect work positions, and generating a GDP of $28 billion. It was, at that time, the same size as the GDP of Uruguay. This leap forward took place mainly in the central-southern region of the country, confirming a tendency that showed signs since the mid-20th century. While in the northeast, the area of land used for sugarcane farming remained the same during the first decade of the 21st century – much of which is restricted to sugar production –, states in the southeast and central-west added 4 million hectares of plantations during this time, doubling the initial total area. States with less tradition in sugar planting, like Minas Gerais, Goiás and Mato Grosso do Sul, joined São Paulo and also transformed themselves into leaders of the national sugar-energy revolution. This phenomenon occurred mainly in small municipalities formerly dedicated to ranching and grain production. Affected by the falling prices of cattle, soy and corn, many producers sought to invest in ethanol, almost always reusing land formerly employed in ranching – extensive, flat, cheap and with soil that is favorable for growing sugar cane. Another factor which contributed to the sugar energy industry boom in the country was the external demand for energy sources that would reduce the dependence on oil and, at the same time, emit less pollutants. In the first decade of the 21st century alone, over 30 countries followed Brazil’s pioneering example and established minimal quotas for biofuel, whether optional or mandatory, added to the gasoline sold at gas stations. It was the ideal opportunity for Brazilian ethanol, touted as the cleanest and most efficient in the world, to conquer the international market. And that’s how it happened: the volume in exports, which hovered around zero in the 1990s, reached 5 billion liters in 2008, the peak year for the sector’s expansion. Still, this figure would not have been achieved if sugarcane ethanol didn’t correspond to the demands of developed nations, mainly in regards to environmental impact. And, in this sense, Brazilian biofuel has several advantages over the rest. Starting with the level of greenhouse gas emissions, which can be as much as 89% lower when compared with gasoline. Corn ethanol produced in the U.S., for instance, is capable of reducing these emissions by up to 38%. Biofuels made from wheat and beets have reached respective maximum levels of 52% and 69%. To obtain this result, it took the combined effort of mill owners, aware of the need to invest in technology and implement new sustainable production models, and the four existing research centers in the country, responsible for conducting studies in genetic improvements with aims of creating varieties that are more and more productive and resistant. But some also attribute the merit to sugarcane itself, said to be one of the most effective photosynthetic plants in the plant kingdom. This means that sugarcane is able to convert a large volume of solar energy into biomass, the equivalent of 20 kilos per square meter exposed to sunlight. This efficiency, added to other factors throughout the chain, guarantees sugarcane ethanol a productivity of around 7000 liters per hectare, almost double that of the corn fuel produced in the U.S. The overall effect is mainly seen in the use of land. Though the total land area used to grow sugarcane in Brazil nearly doubled in the ten years that followed the introduction of flex cars (from 5.4 million hectares to around 10 million), sugarcane plantations came to occupy just 3% of the country’s farmland. In this way, the inherent risks in agribusiness, such as the reduction of vegetal coverage and the competition for land that would be otherwise designated for food production, are minimized here. To reinforce this fact, the government introduced, in 2009, the Agri-Ecological Sugarcane Zoning Program, a strategy which set guidelines for the expansion of plantations. Among the proposed measures are the prohibition of farming in such areas as the Amazon, the Pantanal and Indigenous Lands. An even more rigorous initiative came from the São Paulo state government, introduced in 2007 with the objective of regulating and modernizing the production chain in São Paulo. Christened the Agri-Environmental Protocol, the action proposed a series of directives, to be carried out in the short term, leading to a reduction in the impacts of the sugar-energy sector on the environment. With the ecological demands of importer nations in mind, over 170 producers voluntarily adhered to the protocol, implementing practices which included the protection of water springs, the recuperation of shoreline vegetation, the reuse of the residues from mills for the production of organic fertilizers and, first and foremost, an end to the burning of sugarcane for harvest. Burning is an old-fashioned method, inherited from the colonial era, which intends to facilitate the manual cutting of sugarcane, since it incinerates the leaves, thus leaving behind only the plant stalks. And, since it’s also a practice that produces more pollutants, its extinction was established as a priority by the Agri-Environmental Protocol. According to it, the sector has set a deadline of 2017 to completely eliminate the practice of setting fire to to crops in São Paulo, anticipating the goal set by state legislation, which stipulates the year 2031. Six years after the protocol was signed, 7 million hectares were spared from burning. In environmental terms, this means 4.4 million tons less greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. The same quantity that about 77,000 buses emit in a year of circulation in a city like São Paulo. Abolishing the burning of sugarcane also served as a stimulus to ending manual cutting, at least in regions where less steepness allows for the use of machines. As such, to the same extent that flex cars have taken over the country’s streets and highways, the harvesting machines have spread throughout the fields of São Paulo. In the 2013/2014 harvest, 83% of São Paulo’s sugarcane crops were harvested mechanically. From a labor point of view, this means the end of sugarcane cutters, said to be one of the hardest jobs in the country, due to the extreme work conditions to which employees are habitually subjected. Studies estimate the average work-span for sugarcane cutters to be just 12 years – the same as slaves in colonial Brazil. This is why, in 2009, the federal government announced the National Commitment to Improving Sugarcane Labor Conditions, a fundamental measure for assuring quality of life for sugarcane cutters in places where mechanical harvesting hasn’t yet been implemented. On the day on which it was introduced, the document was signed by three fourths of the companies in the sector in the country, committing themselves to a series of good labor practices, among them hiring by legal contract, support to migrant workers and the promotion of healthcare. In the regions of Brazil where sugarcane cutters were substituted by mechanical harvest machines, a new challenge emerged: accommodating the mass of workers whose manpower was no longer needed to harvest crops. Considering that one machine does the work of 80 cutters, the impact on the number of jobs reaches as high as thousands. In order to prevent these laborers from migrating to areas where crops are still harvested manually, Unica (The Sugarcane Industry Union), in partnership with other organizations and companies, created the RenovAção project, a program of professional re-qualification dedicated to training thousands of former cutters, qualifying them for new and better-paying positions. People who used to cut sugarcane crops by hand now operate GPS-equipped harvesting machines. PLASTIC, DIESEL, ELECTRICITY AND GAS – ON THE NEW FRONTIERS, THE ANSWER TO THE CRISIS The ethanol fever was intense but brief. Just five years after the introduction of flex cars, Brazil’s sugar-energy industry suffered its first big setback, provoked by the worldwide financial crisis of 2008. From that year on, mill owners saw their exports fall and a reduction in available credit and lines of financing, which ended up compromising the renovation of sugarcane crops – a factor that’s essential in maintaining productivity. The second setback came in the fields: extreme weather in the years that followed the crisis, as well as long periods of drought or frost, led to breaks in successive harvests. Additional blows came due to public policy. While the federal government’s incentives for ethanol were clear during the years of euphoria surrounding the flex revolution, the same was not true after the discovery of pre-salt reservoirs, when the focus of investments returned to oil exploration. At the same time, as a way to contain inflation, the government decided to freeze the price of gasoline at refineries, reducing the competitiveness of ethanol. To be advantageous, the price of sugarcane fuel must be a maximum of 70% of the price of gasoline, since its energy efficiency is lower. With the official measure, this margin fell and millions of owners of flex vehicles started filling their tanks with gasoline. Between 2009 and 2013, consumption of hydrous ethanol in the country fell by almost half. The result? Almost a third of the mills were stricken by debt, over forty closed and many others were sold to international groups. Brazil’s sugar-energy industry, which began the century entirely Brazilian-owned, reached a percentage of 40% foreign participation in 2013. There were advances in the midst of the crisis, however, they mainly concerned the international market. In 2010, the U.S. government, in a groundbreaking decision, determined that Brazilian ethanol was the “advanced” kind, meaning that it was capable of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by at least 50%, according to calculations stipulated by the U.S. legislation. In practical terms, they opened the doors so that sugarcane alcohol would be guaranteed a considerable portion of the U.S. market, as foreseen by the Renewable Fuels Standard, a government protocol which establishes progressive quotas for biofuels by the year 2022. According to this program, of the 136 billion liters of renewable fuels to be consumed that year, 15 billion must be of the advanced type. Brazilian ethanol is the only one classified in this category. In late 2011, the United States took another step forward, removing an additional tariff imposed on imported ethanol which had been in effect for the past 30 years. It was the only remaining barrier blocking Brazilian biofuel from conquering the U.S. market once and for all. In fact, in just one year, the volume of exports soared from 650 million liters to around 2 billion. Therefore, the new challenge was in increasing production, weakened at the time by the financial crisis, in order to meet this new demand. The years of crisis in the sector also were ones of searching for new ways to improve the efficiency and productivity of mills. As such, at the same time the industry witnessed decelerated growth, a wide variety of research fronts turned to developing technology that allowed for an increase in crop yields and diversification of products derived from the processing of sugarcane. In this sense, byproducts from sugarcane harvesting and processing – such as bagasse, leaves and straw – became the newest key piece in the sugar-energy revolution. They had been used since the early 20th century in the cogeneration of energy inside the factories: the burning of bagasse releases heat, electricity and the driving force for the production of sugar and ethanol. This makes Brazilian sugar mills 100% self-sufficient in terms of energy and also environmentally clean, since this process doesn’t release pollutants such as sulfur. In addition, bagasse can be a source of additional income for mills, being that excess electricity is sold to the power grid. This is what took place systematically from 2005 on, when electricity generated by biomass was accepted at auctions for new energy for the first time. That year, a little over 1000 GWh was sold to the power grid. In 2013, 15,000 Gwh was sold, resulting from energy that was not utilized for the production of sugar and ethanol. In practical terms, this is equivalent to 8 million homes powered by sugarcane bagasse. And this number could be much higher if auctions were more advantageous for biomass – for example, its cost is higher than that of wind energy. Even still, gradually, the bio-electricity of sugarcane has been establishing itself as a solution not only for the ethanol crisis – from the mills’ point of view – but also for the crisis in supplying hydro-electrical plants, being that this energy can be generated even during droughts. Studies indicate that, by 2022, the energy produced from sugarcane bagasse in Brazil will be the equivalent of the two Belo Monte power plants. In addition to generating electricity, bagasse also emerged as an effective alternative to the production of alcohol. In 2014 in the state of Alagoas, the first plant in the country specialized in cellulose ethanol – a fuel produced from sugarcane byproducts which allows for the multiplication of crop yields without requiring larger plots of land or an increase in the volume of production. This means that, with the transformation of cellulose into alcohol, it is possible to produce 30,000 liters of ethanol for every hectare of crops – four times more than conventional ethanol. Another byproduct from the processing of sugarcane that had attracted attention is vinasse, traditionally used as a fertilizer for crops and, now, transformed into biogas. The method is bio-digestion, the same one used to convert organic garbage or animal waste into gas. Thanks to the action of bacteria, vinasse is decomposed and transformed into methane, which can be used as a substitute for cooking gas or automobile fuel and can also generate electricity. In 2012, the implementation of a mill in Pernambuco introduced the commercial production of sugarcane biogas in the country, with a capacity to generate 612 MWh of electrical energy per month. Therefore, despite the crisis in the sector, what we have seen in the second decade of the 21st century has also been the multiplication of the possibilities of sugarcane to go beyond just sugar and ethanol. This is the case with plastic, which has also taken over the market in these years. It all started with the plantbottle, a recyclable bottle introduced by Coca-Cola in 2010, whose composition contains 30% plastic derived from ethanol. In the same year, Braskem opened a factory of green polyethylene, also produced from sugarcane alcohol and 100% recyclable. In a few short years, it became the raw material used to package over 50 products from brands like Tetrapak, Danone, Natura and Faber-Castell. And there is also Biocycle, a polymer derived from the fermentation of sugar by bacteria which promises to be entirely biodegradable when it reaches the market. Placed in the natural world, it takes just one year to decompose. Conventional plastics take centuries. This is the last frontier in the sugarcane industry: the transformation, through biotechnology, of a source of vegetal origin into molecules which, for decades, only oil was capable of producing. It is the era of bio-hydrocarbons, developed, much like green plastic, from the actions of micro-organisms genetically modified over the process of sugar fermentation. In other words, the same sugar which, in the past, drove the economy of colonial Brazil is today the raw material for the production of diesel, kerosene and gasoline – all derived from sugarcane. The three fuels are derived from the same component, farnesene, a hydrocarbon developed by the American company Amyris which also allows for the manufacturing of tires, skin moisturizers and perfumes. Of the three, diesel is the one in the most advanced stage, being that, since 2011, it has been fueling part of the fleet of city buses that circulate in São Paulo, mixed with ordinary diesel at a proportion of 10%. This mixture, though small, guarantees emissions of 80% less pollutants than a tank of diesel derived from petroleum. Meanwhile, bio-kerosene was first tested in 2012, when a plane operated by the airline Azul took flight with half of its tank filled with sugarcane fuel. This was the first step towards the international standards organization ASTM approving the use of sugarcane kerosene in commercial flights abroad, also at a proportion of 10%, in 2014. When it comes to gasoline, studies in several countries took determined steps to make commercially viable the transformation of sucrose into a combustible fuel similar to the one derived from oil. In the United States, Shell is already running a pre-industrial plant. When bio-gasoline does finally reach the market, it won’t just be more efficient than ethanol, but it also will no longer require the use of flex engines. It will be, at last, the beginning of the era of green oil. |